PEFinder: Container Based Classification of Pulmonary Embolism

01 Dec 2016The reproducibility crisis does not just impact academia, it’s an issue for clinical research applications as well. In 2011 Brian Chapman published a rule-based classifier called PEFinder that has become the standard in the field for classification of pulmonary embolism. At Stanford I have been working with a group of radiologists to reproduce this work, and our starting point has been the core software developed by Chapan, including pyConTextNLP and radnlp. A quick shout out to Chapman for bridging the challenging gap between the clinical and research world, and producing a robust set of Python modules for working with clinical text. The fact that his research practices were very reproducible (providing instructions, robust documentation, and versions of software) made PEFinder an easy, fun, and great first go at container-izing a clinical research tool. And guess what? Take a look at the picture below - we are going to generate the same application and run it with Docker and Singularity containers! Let’s go!

PEFinder Containers

Installing dependencies is always challenging, because the chance that your local machine looks like Brian’s, or anyone else’s, is very small. Regardless, it should be a standard that I can plug my own data into a research tool and get a result, seamlessly, without needing to install dependencies, and debug errors in that process. Since Singularity is actively growing and taking the HPC world by storm, I decided to bring it into this clinical context. In this recipe, I will detail some of the basic steps of migrating a clinical application into a reproducible product.

Prediction of Pulmonary Embolism: an example application

I have wrapped the core functions developed by Chapman in Docker and Singularity containers, with complete instructions and details available at vsoch/pe-predictive.

Development Strategy

For this application, you will see that I took the following strategy:

Keeping the Python simple

The python scripts aren’t a proper python module, but a set of scripts in the pefinder folder. There is one executable, cli.py, which stands for “client” and this is the script that takes input arguments and directs them to functions in the other files. The main file that has the guts of the analysis is pefinder.py, and it brings it utility functions from utils.py. The point here is that

You don’t need to know how to create a “proper” module to practice reproducibility.

“Real” python modules installed via pip are ideal, but if it’s going to stop you from pursuring creating a container (it takes too much time, etc.) then just skip it. I’ll note that creating a “real” module isn’t so bad once you try it once.

Killing two containers with one stone

A Singularity container can be built from a Docker container. I can run a Singularity container in a cluster environment (meaning on larger datasets that might not fit on my local machine). I can’t run Docker in those places. So it makes sense to make a Docker container, and then build a Singularity one from it. Two containers, one stone! And interestingly:

Competing applications that support one another are most successful in the end.

Using publicly available repositories

I want version control, meaning a record of all the changes to my code, and so the repo is going to live on Github. The Docker image is built automatically when I push here, and this is done by connecting the repo to Docker Hub. Both of these are free to use, for us academics that can’t afford things.

Introducing the Containers

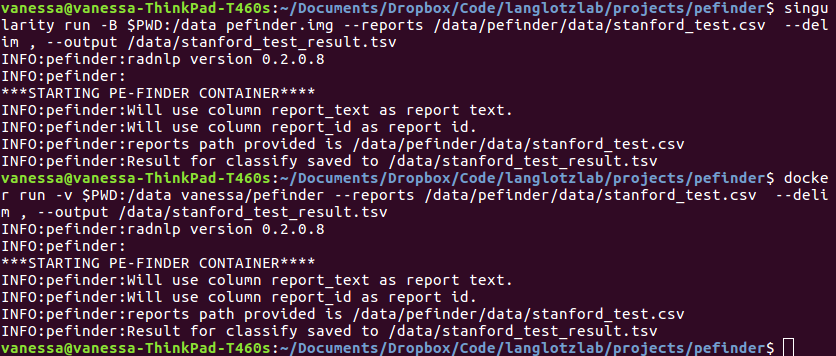

If you aren’t interested in details, here are side by side examples of running the analysis for each container. It’s beautiful how similar they come out to be:

# Docker

docker run -v $PWD:/data vanessa/pefinder --reports /data/pefinder/data/stanford_data.csv --delim , --output /data/stanford_result.tsv

# Singularity

singularity run -B $PWD:/data pefinder.img --reports /data/pefinder/data/stanford_data.csv --delim , --output /data/stanford_singularity_result.tsv

The main difference has to do with the parameter used to map a volume, Docker uses -v (volume) and Singularity uses -B (bind). In this example, that seems to be it. In the Docker example, we are running the image referenced by vanessa/pefinder, which Docker downloads to your machine as a bunch of layers from the Docker Registry, and Singularity points to an actual image sitting in a folder called pefinder.img.

Docker

The primary driver of Dockerland is the Dockerfile, and for our PEFinder Docker image, you can look at the Dockerfile to see that we install the Python dependencies mentioned above, along with adding the proper files to the container. After you install Docker, you will want to run the container. If you want to run the container hosted on Docker Hub, then you can skip this next instruction. If you want to build the container locally first:

git clone http://www.github.com/vsoch/pe-predictive

cd pe-predictive

docker build -t vanessa/pefinder .

An important distinction if you look in the file, you will see this thing called ENTRYPOINT:

ENTRYPOINT ["python","/code/pefinder/cli.py"]

This is a really important thing to notice, because it should be distinguished from the similar CMD. An entrypoint is meant to be executed when the container is run, and this maps directly to the Singularity runscript. (I think) that a command is something that is run, but doesn’t get handed to your machine as the current process. I’m not entirely sure how it works, but I find that when I use an entrypoint, any following input arguments are passed seamlessly (without needing to add extra catches for them, e.g. "$@") and likely if I looked, the running process of the script would be the container. I think this would be different from having the script running as a different process inside the container process. I’m not totally sure about this, I’d love to know the details if anyone is privy - please comment below! For our purposes, I’ll reiterate that (probably) an entrypoint is what you want to run an application from the outside.

Singularity

This image is built by dumping those same Docker layers into a Singularity image, after installing Singularity of course.:

sudo singularity create --size 6000 pefinder.img

sudo singularity bootstrap pefinder.img Singularity

The first command creates the image container, and the second bootstraps a build file called Singularity to populate it with a file system and applications, in this case, everything we put into the Docker image. Let’s take a look at the Singularity build file - they are really easy to make!

Bootstrap: docker

From: vanessa/pefinder

%runscript

cd /code/pefinder

exec /opt/conda/bin/python /code/pefinder/cli.py "$@"

%post

chmod -R 777 /data

echo "To run, ./pefinder.img --help"

For a docker bootstrap, the only part that you really need is the header that specifies docker and the image From: vanessa/pefinder. The bootstrap will automatically use the ENTRYPOINT as the runscript, adding exec at the beginning to execute the command as the main process, and $@ at the end to handle additional input arguments. Why did I edit the command? It’s because the Singularity bootstrap process does not preserve the WORKDIR command. This means that we need to run cd /code/pefinder first. Don’t worry, I’ve created an issue for this and will be working on it soon.

The image creation and bootstrap process looks like this:

sudo singularity create --size 6000 pefinder.img

Creating a new image with a maximum size of 6000MiB...

Executing image create helper

Formatting image with ext3 file system

Done.

sudo singularity bootstrap pefinder.img Singularity

Bootstrap initialization

Checking bootstrap definition

Executing Prebootstrap module

Executing Bootstrap 'docker' module

From: vanessa/pefinder

Cache folder set to /root/.singularity/docker

Extracting /root/.singularity/docker/sha256:a3ed95caeb02ffe68cdd9fd84406680ae93d633cb16422d00e8a7c22955b46d4.tar.gz

Downloading layer sha256:6db6d8df4afc785cfcfce8fd0ce9997d85dafea1b6c4520b6e83761715f963dc

Extracting /root/.singularity/docker/sha256:6db6d8df4afc785cfcfce8fd0ce9997d85dafea1b6c4520b6e83761715f963dc.tar.gz

Downloading layer sha256:48f30034229d5c18d8f8edd8f197c79fc6e270cbb1a660224315fa15a54d36be

.

.

.

+ echo To run, ./pefinder.img --help

To run, ./pefinder.img --help

Done.

Running things

You can ask for help for either of the containers with --help to get details about running things:

./pefinder.img --help

# Docker docker run vanessa/pefinder --help

INFO:pefinder:radnlp version 0.2.0.8

usage: cli.py [-h] --reports REPORTS [--report_field REPORT_FIELD]

[--id_field ID_FIELD] [--result_field RESULT_FIELD]

[--delim DELIM] --output OUTPUT [--no-remap]

[--run {mark,classify}]

generate predictions for PE for a set of reports (impressions)

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

--reports REPORTS Path to folder of reports, or tab separated text file

--report_field REPORT_FIELD

the header column that contains the text of interest

(default is report_text)

--id_field ID_FIELD the header column that contains the id of the report

(default is report_id)

--result_field RESULT_FIELD

the field to save pefinder (chapman) result to, not

saved unless --no-remap is specified.

--delim DELIM the delimiter separating the input reports data.

Default is tab (\t)

--output OUTPUT Desired output file (.tsv)

--no-remap don't remap multilabel PEFinder result to Stanford

labels

--run {mark,classify}

mark (mark), or classify (classify) reports.

I won’t go into the details of the argument specification, for that you can see the Github repo README, however I’ll note that the executable makes the containers flexible to do different things (mark reports, or classify reports), and also to specify differences in the input (for example, changing the default column name of report_text to something else. Finally, the application is flexible to handle a folder of single reports, or reports represented in a single text file. Note that I only have only done the latter, so the first is not tested. If you test the folder import and find a bug, please report an issue.

Classifying Reports

Classifying reports means marking and classification. This is default.

# Docker

docker run -v $PWD:/data vanessa/pefinder --reports /data/pefinder/data/stanford_data.csv --delim , --output /data/stanford_result.tsv

# Singularity

singularity run -B $PWD:/data pefinder.img --reports /data/pefinder/data/stanford_data.csv --delim , --output /data/stanford_result.tsv

INFO:pefinder:radnlp version 0.2.0.8

INFO:pefinder:

***STARTING PE-FINDER CONTAINER****

INFO:pefinder:Will use column report_text as report text.

INFO:pefinder:Will use column report_id as report id.

INFO:pefinder:reports path provided is /data/pefinder/data/stanford_data.csv

INFO:pefinder:Analyzing 117816 reports, please wait...

Adding --run classify would do the equivalent.

Marking Reports

This is an intermediate step that won’t give you classification labels. You might do this to look at the data. The markup is output in the field markup of the results file.

# Docker

docker run -v $PWD:/data vanessa/pefinder --run mark --reports /data/pefinder/data/stanford_data.csv --delim , --output /data/stanford_result.tsv

# Singularity

singularity run -B $PWD:/data pefinder.img --run mark --reports /data/pefinder/data/stanford_data.csv --delim , --output /data/stanford_result.tsv

Shelling into containers

In the example above, we use the containers like executables. They are summoned to run, and then perform a function, and then spit out the output and go away. It could be the case that we want to run the python console interactively. How do we shell into the containers?

Singularity Shell

Singularity has an easy, intuitive way to shell inside!

singularity shell pefinder.img

If you want the container to be writable (default isn’t) then you will need root (on your local machine) and add the --writable option:

sudo singularity shell --writable pefinder.img

Singularity: Invoking an interactive shell within container...

Singularity.pefinder.img> cd /code

Singularity.pefinder.img> ls

Dockerfile README.md docker-compose.yml pefinder

LICENSE Singularity docs

You can then proceed as follows, and all of the dependencies for radnlp and the application are installed. For example:

singularity shell --writable pefinder.img

Singularity.pefinder.img> cd pefinder

Singularity.pefinder.img> ls

cli.py data logman.py pefinder.py utils.py

You might run the analyses via the python terminal, and in this case you must be careful to specify the python in the container, as you may accidentally call your machine’s python specified via an environmental variable:

/opt/conda/bin/python

Python 3.5.2 |Anaconda 4.2.0 (64-bit)| (default, Jul 2 2016, 17:53:06)

[GCC 4.4.7 20120313 (Red Hat 4.4.7-1)] on linux

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> from pefinder import analyze_reports

INFO:pefinder:radnlp version 0.2.0.8

For details on the functions, you can look at the code. You may also want to use the same command line executable, but from inside the container!

Singularity.pefinder.img> /opt/conda/bin/python cli.py --help

INFO:pefinder:radnlp version 0.2.0.8

usage: cli.py [-h] --reports REPORTS [--report_field REPORT_FIELD]

[--id_field ID_FIELD] [--result_field RESULT_FIELD]

[--delim DELIM] --output OUTPUT [--no-remap]

[--run {classify,mark}]

generate predictions for PE for a set of reports (impressions)

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

--reports REPORTS Path to folder of reports, or tab separated text file

--report_field REPORT_FIELD

the header column that contains the text of interest

(default is report_text)

--id_field ID_FIELD the header column that contains the id of the report

(default is report_id)

--result_field RESULT_FIELD

the field to save pefinder (chapman) result to, not

saved unless --no-remap is specified.

--delim DELIM the delimiter separating the input reports data.

Default is tab (\t)

--output OUTPUT Desired output file (.tsv)

--no-remap don't remap multilabel PEFinder result to Stanford

labels

--run {classify,mark}

mark (mark), or classify (classify) reports.

Docker Shell

Docker has a similar way to shell inside the container:

docker run -it --entrypoint /bin/sh vanessa/pefinder

Since your local environment isn’t mounted by default, the default python should be the one we installed, /opt/conda/bin/python

Why?

This post aims to do things. First, to encourage you to think about containers in not just a research context, but also a clinical one. As currently implemented, this same container could do the following:

- run locally to analyze one or more reports

- run on a cluster to analyze many more reports in parallel

Now imagine that we add a simple web interface (see this post for examples of using web and singularity) that would provide a view in a clinical context to copy some report, and get a classification. I think this a great idea, and in fact I’m going to be pinging Brian about how he might want this interface to look. This particular example with pulmonary embolism might not be the most relevant in the case of “on demand clinical diagnosis,” but having some other clinical data (e.g., results from a blood test) as an advisor to do additional testing might be.

What did I learn?

The transition between Docker and Singularity is very smooth, but not entirely seamless. Here are a few things to keep in mind when you do the conversion:

- The Singularity container currently does not have an understanding of the Docker

WORKDIR. If the application depends on being in a particular location to shell or run, you might want to add acdto the runscript. - Singularity includes the user’s

$HOMEdirectory and environment, so things like a custom python path can be called in the container (instead of the container’s intended python). For this reason, I recommend specifying the complete path when calling an executable in the runscript. - Keep privacy in mind. The data used to generate the rule-based model is not included in the containers, or any of the repositories to generate them. This becomes much more salient as you move into clinical research.

- There is no “best” container, each has pros and cons, and different use cases. The best strategy is to build portable products that can be mapped seamlessly between not only infrastructures (cloud vs. HPC) but also containers (Singularity vs. Docker vs. something else).

Next Steps

Cite PEFinder

If you use these analyses in your work (which is the intent in providing containers for them) please cite the work, and look at the code bases, provided by Chapman et. al:

How can we extend these tools?

Do you have an analysis or tool that you’d like to see in a container? Let’s make that happen! If you have finished applications, or ideas for clinical or research applications that might be deployed at scale, or deployed within a hospital, using containers, or if you want advice and help with anything that falls in the bucket of “research application” I want to hear from you! Please don’t hesitate to reach out or contact me directly.